The Usefulness of Measurement Tools

At Solace we make use of a number of standardized measurement tools – quantified assessments of psychological and emotional well-being or distress. There are always challenges converting subjective information into data that can be measured and it is important to remember both what it can be useful for and also the constraints and limitations on how it can be used.

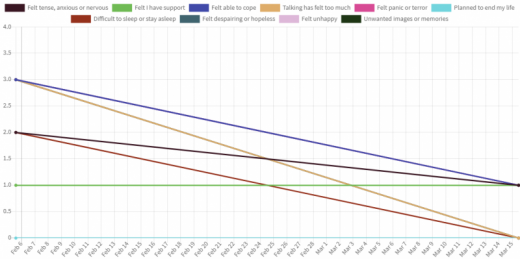

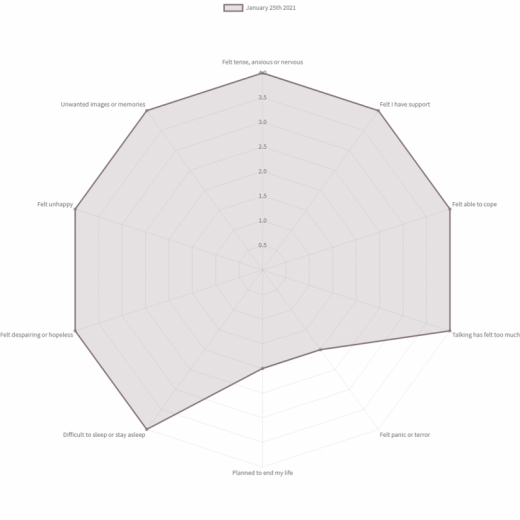

If assessment is done at regular intervals it can be useful to see, for both therapist and client, if over time a client’s experience of the world and their life in it has improved or deteriorated or remained stable. If there have been significant changes in any aspect, such as hopefulness, or feeling supported for example, it can lead to useful conversations about what has been helpful in therapy, and what less so, and what external factors may have affected the changes.Â

I have found it particularly useful when it highlights for clients lifestyle choices they have initiated themselves that have had beneficial effects on their well-being.

For a therapist to use the data in the context of a client they are working with is one thing, but when it comes to data being used externally and divorced from the qualitative dimension of assessment there can be more significant difficulties. I have had two illustrations of this in my own work.

In the first instance, an asylum-seeker client who had for many months, as far as formal assessment was concerned, had been moderately distressed but stable, had what I would describe as a spiritual or ‘peak’ experience. They had been taken on a camping trip in the countryside by a couple of compatriot friends and during this had had a transformative joyful experience of connection with nature and with the ‘wild’, with God and with a sense of meaning for life. It had also strongly evoked the traditional mountain life of their childhood. In the few weeks after that an assessment showed an improvement to around a third of his previous distress levels, and certainly better than I would score myself on an average day. I was cautious in my expectations for them, aware that peaks are peaks and the only way from the top is down. The objective data indicated they deteriorated a little after that. But actually, that too was true of a ‘peak’ experience. They did come down, some of the previous stresses re-emerged, but there had also been a permanent improvement from before. Something had happened that they could not forget. The nature of our conversations changed, they needed less from me, and a few months later, but still as an asylum seeker, we finished the counselling sessions.

The second example concerns a refugee client, not in a good position at the start, whose assessment scores showed a slow improvement over about a year, to what seemed to be a relatively stable level. But then in the course of a few weeks they plummeted to being far more distressed than they were at the start. That is an assumption because by that stage it was impossible even to conduct an assessment. They withdrew completely and care was passed on to the NHS crisis team. It only emerged afterwards that the client had transferred countries with a supply of psychiatric drugs no-one knew about. Eventually the supply ran out and the client bravely tried to come off them, without telling anyone. After medical intervention, stability returned slowly. As far as assessment scores are concerned, getting back to where they were six months ago would feel like a good result.

Two extreme examples I know, but to objectively look at quantitative data would beg the question ‘what happened there?’ On its own it is inadequate to say very much about my own, or Solace’s work, or clients’ progress in surviving or rebuilding their lives.

Paul Wood – Solace Therapist